“Henri Storck at the crossroads of life” by Luc de Heusch

Henri Storck at the crossroads of life

Luc de Heusch

Henri Storck learned the aesthetics and ethics of his works from Flaherty’s films: rigorous, based on reality, but subject to the rules of staging. He was twenty years old when he discovered and marvelled at Moana at the cinema club in Brussels. He created a film club in Ostend and started filming his native city with the candid eye of an amateur.

Henri Storck learned the aesthetics and ethics of his works from Flaherty’s films: rigorous, based on reality, but subject to the rules of staging. He was twenty years old when he discovered and marvelled at Moana at the cinema club in Brussels. He created a film club in Ostend and started filming his native city with the candid eye of an amateur.

Equipment and technique would be perfected with the passage of time, with the very history of cinema, and in over half a century, Storck explored the whole field of the documentary. He did not yet know, although Flaherty had shown him the way, that he would become one of the masters of anthropological film.

The young Henri Storck became official cinégraphiste of the city of Ostend in 1930. He developed his own negatives in the laboratory he had set up and in the evening he would show his newsreels in a cinema in town, with orchestral accompaniment. He also worked diligently in the shoe shop he had inherited from his father in the rue Buyl. He kept rigorous accounts while at the same time he took pleasure in caressing, with a professional touch, the feet of pretty ladies. A selection of these early images was brought together in Ostend, reine des plages, for which Jaubert wrote his first music for film (1930). But above all, he undertook as a solitary experimenter, a series of poetical essays that appeared at the time to be quite unusual, such as the series of visual variations on the theme of the sea, the wind and the sand, modestly entitled Images d’Ostend (1929 – 1930). He showed these fascinating seascape images during the second International Congress on Independent Cinema that was held in Brussels in December 1930, and Jean Vigo, who was there to present A propos de Nice, cried out in amusement: So much water, so much water! It was to be the beginning of a firm friendship.

Germaine Dulac was also a participant in this meeting. She was director of the company Gaumont Franco-Film (G.F.F.A.). She hired the two young men as assistants and invited them to come and work with her. And so, off went Henri Storck, first to Paris, then to Nice where he met up with Vigo again. He returned to Ostend during the summer of 1931 where he directed a marvellous, completely eccentric little film, which defies classification, being half fiction, half dream: Une idylle à la plage. He went off to Paris to put a soundtrack to these amazingly free images and became Vigo’s assistant on Zéro de conduite. He made a brief appearance on screen in a cassock.

He returned to Ostend where Eclair Journal gave him the job of directing an uninteresting commission using its archives. It was to be a film dedicated to the glory of sport. Storck accepted on the condition that he could use other images for his own ends. It is this exchange of favours that made possible one of the most virulent antimilitarist works in the history of film: Histoire du soldat inconnu (1932). In a comical and merciless montage, Storck gathered together news images filmed in 1928 – 1929, just after the signing of the Briand-Kellog pact that claimed to outlaw war. He thereby restored to these falsely objective documents their true meaning: it was suddenly possible to see the men in high places as they really were – ridiculous and fearsome. This little film was naturally banned for a long time by French censorship as an insult to the army.

He returned to Ostend where Eclair Journal gave him the job of directing an uninteresting commission using its archives. It was to be a film dedicated to the glory of sport. Storck accepted on the condition that he could use other images for his own ends. It is this exchange of favours that made possible one of the most virulent antimilitarist works in the history of film: Histoire du soldat inconnu (1932). In a comical and merciless montage, Storck gathered together news images filmed in 1928 – 1929, just after the signing of the Briand-Kellog pact that claimed to outlaw war. He thereby restored to these falsely objective documents their true meaning: it was suddenly possible to see the men in high places as they really were – ridiculous and fearsome. This little film was naturally banned for a long time by French censorship as an insult to the army.

This was Storck’s first foray into the field of social criticism. It was a passion that would never leave him. In that same year, 1932, misery fell upon the workers following the great economic slump. In the Borinage a hundred thousand workers went out on strike in protest against a reduction in salary, and the government responded brutally by sending in the troops. The following year, André Thirifays and Pierre Vermeylen asked Henri Storck to make a film denouncing the degradation of men, revolt, and repression. Storck was 26 years old. To carry through such a serious subject he called on one of his elders, Joris Ivens, for help. He had met him at the International Congress for Independent Film and together they filmed the classic in the history of social documentary: Misère au Borinage (1933). A year after the tragic events of 1932, the workers opened the doors of their hovels to the deeply moved filmmakers and acted out their own tragedy.

In contrast to Ivens, Storck was not a revolutionary. Nevertheless, the slightest injustice sickened him and he was convinced that it was possible to change this world corrupted by money. Just as committed, but in a different manner, is a film dating from 1937. Commissioned by a very official body, the National Society for Low-Price Housing, Maisons de la misère is an almost unbearable testament to slum conditions, which people were working to eliminate at the time. To quote the sociologist Henri Janne who commented on the film when it was launched: Merciless, it spares us nothing; the viewer is tense from watching this unimaginable poverty, the unbelievable decline of man, but nevertheless follows the document to the end because he/she is captivated by its rhythm. The indignity of the slums is thrown in all our faces, yours and mine, for we unconsciously accept its existence.

Storck was a warm-hearted reformist. His absolute sincerity was that of an intransigent artist whose rebellious conscience is deaf to slogans, whatever they may be. I am full of admiration for a film that would only be a banal report on the funeral of a political man, if it were not that of Emile Vandervelde, the leader of the Belgian socialist party, and one of its founders. Henri Storck was able to film with rare intensity these images of exceptional collective emotion, which probably no contemporary statesman would be able to provoke on his final day. Le patron est mort (1938) is the title of this poignant film. In this report, as in more elaborate documentaries, the filmmaker modestly remains in the background, the better to make his subject stand out. Such was the secret of great painters in the Middle Ages. Great creator of images that he was, I would happily place Henri Storck in their tradition. As Jean Queval stressed, Storck travelled through all the history of the cinema. He was ever attentive to all the technical and stylistic changes of this art over a sixty-year period, but always remained faithful to himself. That is to say, faithful to a certain vision of cinema as having a mission to witness the real world, society, man and his work, be he metallurgist, painter or writer.

Storck was a warm-hearted reformist. His absolute sincerity was that of an intransigent artist whose rebellious conscience is deaf to slogans, whatever they may be. I am full of admiration for a film that would only be a banal report on the funeral of a political man, if it were not that of Emile Vandervelde, the leader of the Belgian socialist party, and one of its founders. Henri Storck was able to film with rare intensity these images of exceptional collective emotion, which probably no contemporary statesman would be able to provoke on his final day. Le patron est mort (1938) is the title of this poignant film. In this report, as in more elaborate documentaries, the filmmaker modestly remains in the background, the better to make his subject stand out. Such was the secret of great painters in the Middle Ages. Great creator of images that he was, I would happily place Henri Storck in their tradition. As Jean Queval stressed, Storck travelled through all the history of the cinema. He was ever attentive to all the technical and stylistic changes of this art over a sixty-year period, but always remained faithful to himself. That is to say, faithful to a certain vision of cinema as having a mission to witness the real world, society, man and his work, be he metallurgist, painter or writer.

Storck was at his best when he plunged enthusiastically into a sociological portrait. His masterpiece is Symphonie paysanne, which Henri Langlois admired above all other films. Devoting three years, from 1942 to 1944, to the directing of a serene film on the peasantry while the world around him went crazy, was no mean feat. Storck was in fact carrying through a very old project. A craftsman from old stock, he had a fine-tuned understanding of the gestures of work, such as the English school of documentary had placed at the forefront of its concerns under the impetus of Grierson.

Just fifteen kilometres from Brussels we suddenly discover something like an exotic world, both close and very distant, with a secret daily activity, totally unknown. There were four movements, four seasons, followed by a Noce paysanne. The film is composed as a great slow poem where the life and death of plants, animals, and men are all themes with equivalent, identical weight. This imposing work precedes Rouquier’s Farrebique by two years.

Henri Storck was a witness – sometimes accusing, sometimes not, but always warm-hearted – of his own country. He was an ethnographer of the inner world and a man with an eye on the far distance. Two extreme dates, and two films mark his interest in far away lands. In 1935, he edited the images that the great cameraman Ferno brought back from Easter Island. This desolate place at the end of the world was at that time one the most mythical places for the Western imagination. Ado Kyrou interpreted the film in a somewhat singular manner in his book Le surréalisme et le cinéma. But he was not mistaken to think that the documentary, going beyond reality, here achieves the fantastical: the arrogant, mysterious island raises its question mark in the middle of the ocean, defying the boldest rational explanations.

Henri Storck was a witness – sometimes accusing, sometimes not, but always warm-hearted – of his own country. He was an ethnographer of the inner world and a man with an eye on the far distance. Two extreme dates, and two films mark his interest in far away lands. In 1935, he edited the images that the great cameraman Ferno brought back from Easter Island. This desolate place at the end of the world was at that time one the most mythical places for the Western imagination. Ado Kyrou interpreted the film in a somewhat singular manner in his book Le surréalisme et le cinéma. But he was not mistaken to think that the documentary, going beyond reality, here achieves the fantastical: the arrogant, mysterious island raises its question mark in the middle of the ocean, defying the boldest rational explanations.

Thirty years later, the International Scientific Foundation, created at the instigation of King Leopold III, entrusted Henri Storck with the difficult task of completing the production of an ambitious full-length film constituting a sort of marvellous swan song to Belgian colonialism. In the film, colonisation is set aside to show nature in its free state: men and animals united by close ties, as if by some exceptional grace the Whites had not intervened in their relations. This superb visual poem would not exist if it were not for the organising talent, the global approach and the sensitivity of Henri Storck, whose role as producer was highly creative (Les seigneurs de la forêt, 1958).

Henri Storck turned his eyes once again to his own country and a few years later, from 1969 to 1972, he offered us a vast fresco called Fêtes de Belgique. The first tableau is devoted to the carnival in Ostend, in honour of his own happy childhood. This joyfully mature work is as much a product of a pictorial world as of European ethnography. Storck showed carnivals and processions as an explosion of colours, yet never gave in to the easy option (and triviality) of the impressionistic discourse. Curious about the last vestiges of a popular culture, in which he himself had his roots, he celebrated the pagan triumph of the Gilles, the Chinels and the giants, and the mystery of the planting of the May tree, salutary counterpoints to the procession of Saint-Sang and the penitents of Furnes. He undertook a long and exemplary investigation of folklore, turning to the best-informed advisers. However, he deliberately decided to provide no didactic commentary, giving us the unrestricted pleasure of image and sound.

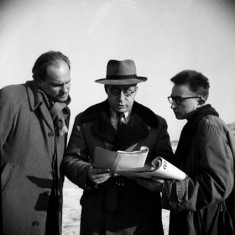

I was lucky enough to be Henri Storck’s assistant in the directing of the short film Au carrefour de la vie, a fictional documentary (1949). I was in charge of documentation. I am indebted to Henri Storck for this, my first lesson in sociology. Heavy-hearted, we watched the sad trials of unloved children. Together we visited sinister places where powerless but well-intentioned group leaders attempted to restore a sense of hope to despairing adolescents who stared at us with hate in their eyes. I had learned from Henri Storck to feel that which none of my teachers at university had taught me: emotion in the face of man’s suffering – and worse still, that of children hunted down by the justice of adults. For all of my generation, who did not go to film school, he was an exemplary master. He taught us patiently, as a master taught his apprentice in the Middle Ages, the spirit and technique of an art that he had taught himself, and in great part invented. His welcoming home was always open to young filmmakers, with the marvellous complicity of Virginia Leirens.

I was lucky enough to be Henri Storck’s assistant in the directing of the short film Au carrefour de la vie, a fictional documentary (1949). I was in charge of documentation. I am indebted to Henri Storck for this, my first lesson in sociology. Heavy-hearted, we watched the sad trials of unloved children. Together we visited sinister places where powerless but well-intentioned group leaders attempted to restore a sense of hope to despairing adolescents who stared at us with hate in their eyes. I had learned from Henri Storck to feel that which none of my teachers at university had taught me: emotion in the face of man’s suffering – and worse still, that of children hunted down by the justice of adults. For all of my generation, who did not go to film school, he was an exemplary master. He taught us patiently, as a master taught his apprentice in the Middle Ages, the spirit and technique of an art that he had taught himself, and in great part invented. His welcoming home was always open to young filmmakers, with the marvellous complicity of Virginia Leirens.

Henri Storck toyed with the idea of many ambitious projects, which reached varying degrees of completion. He involved me in two of these, of which I have happy memories. Firstly, an international inquiry into man’s gestures, of which I had the honour of directing the first chapter by filming Belgian mealtimes, while he himself put the finishing touch to this endeavour by filming deaf-mutes (Les gestes du silence, 1960), then an English dancer, Juana (Variations sur le geste, 1962). The second adventure was particularly comical. With the help of a French producer, André Tadié, Storck organised a reconnaissance expedition to explore the world of gypsies throughout Europe. Two ladies accompanied us: Monique, my girlfriend, and Siska, Henri Storck’s daughter, whom he had the greatest trouble persuading not to fall in love with a handsome dancer in the most sordid suburb of Zagreb. Thanks to this Tintin-like adventure I discovered a certain number of great European cities through their wastelands and police repression. We were almost arrested as spies in Yugoslavia. It is true that our guide and travelling companion was the highly enigmatic Jan Yoors, a Belgian artist living in New York after having spent a large part of his childhood and adolescence, before the war, in the caravan of Pulika, a gypsy aristocrat who became his adoptive father. It was while looking for this strange character, of whom Jan had had no news for several years, that we set out on the roads of Europe for two months in the summer of 1961, covering ten thousand kilometres in a mad race from Paris to Istanbul. We had been foolish enough not to take a camera with us, certain that we would bring back with us a fabulous script about the last nomads of the West, who are convinced, rightly or wrongly, that we have occupied their hunting grounds.

I wrote the script, but André Tadié quickly realised that it would be impossible to carry through. Like La mort de Vénus, one of Henri Storck’s first films from 1930, which has been reduced to dust and is definitively lost, the saga of the gypsies that Storck dreamed about for years, is now nothing more to us than the memory of a wonderful holiday.

Luc de Heusch