“Sixty years of filmmaking” by Jeacqueline Aubenas

Sixty years of filmmaking, seventy films

Jacqueline Aubenas

When one goes back and looks at the early films, it is pleasing to note that in the space of three years, from 1928 to 30, Henri Storck set in place, confidently and instinctively, everything that would be affirmed and deepened as his work developed: the founding themes, his sure and innate relationship with the language of film, this compound eye that scrutinises the world through a different prism, without losing the sensitive unity of the whole vision.

When one goes back and looks at the early films, it is pleasing to note that in the space of three years, from 1928 to 30, Henri Storck set in place, confidently and instinctively, everything that would be affirmed and deepened as his work developed: the founding themes, his sure and innate relationship with the language of film, this compound eye that scrutinises the world through a different prism, without losing the sensitive unity of the whole vision.

One can only dream about the first film in the Queval filmography: Films d’amateur sur Ostende, Pathé-Baby 9.5 format, 1927-28. It will never be seen again. It has disappeared into limbo, into the obscurity due to such early experiments, but already the word ‘film’ is in the plural. Then, there is the term ‘amateur’, which comes from the Latin amare, he who loves. It turned out to be correct in professional terms, as well. And finally, the films are based in Ostend, the port town to which he, or rather his affections, were tied. Everything is set out with the concentration of an apprentice, where even the technical specification of the camera and the format are present, and will henceforth continue to be so.

The sea/matrix

Evidently, the sea is there to give birth to the artist. Even though The Jazz Singer, screened on October 6, 1927, was a ‘talkie’, cinema resisted and remained silent a while longer, devoted solely to images.

Evidently, the sea is there to give birth to the artist. Even though The Jazz Singer, screened on October 6, 1927, was a ‘talkie’, cinema resisted and remained silent a while longer, devoted solely to images.

Making images speak, looking in order to say, to see, to show. The young Storck looked at and related places and people, elements and gestures.

At the very beginning there was the North Sea, amniotic liquid, the song of the sirens that gave him common ground with Ensor and Delvaux. Already the vision is shared, not in the cinematographic sense of things, but in terms of a shared point of view. Henri Storck, aged just over 20, made his plans .

He observed the sea, filmed it, and discovered his own scale of shots, the relationship between shots, the interplay of a language. In Images d’Ostende, he built a conceptual fiction where each title card, since this is silent film, placed us in the very meaning of a narrative vision: he sketched the portrait of a character and gave this character a field of action. The North Sea became a cinematographic figure as defined by Tarkovsky, a site of uniqueness, of visible truth. This figure of the landscape, be it the sea or some other, would become a constant feature of Storck’s films. He observed and set down shot after shot, as would a writer, word after word. The descriptive function of cinema is rarely established for its own sake, that is to say outside of the context of a story or conveying some information, presented as pure poetry. This relationship with the elements, water, sky, earth, etc., introduced in the very first film, would henceforth become a constant theme of exploration.

In Une pêche au hareng, a parallel line of investigation was established, that of the history of gestures, a fascination for man at work, the recording of a condition, that of the fisherman, the workman, the peasant… Throwing, digging, bending, pulling, pushing, walking, manipulating – Storck presented the movements of labour. He observed men and gave their activities the dignity they were due. He expressed their value, in much the same way as Hugo did in Les Misérables.

Trains de plaisir opens the third theme. The trains go, not unexpectedly, to the coast taking people to bathe in the sea. They open the way to a happy body, to the sensuality of the sand and the sun, to the birth of Venus, to the circulation of the naiads. The sea becomes feminine and Aphrodite emerges from the waves.

A way of looking at things

Pour vos beaux yeux led to another way of observing things.

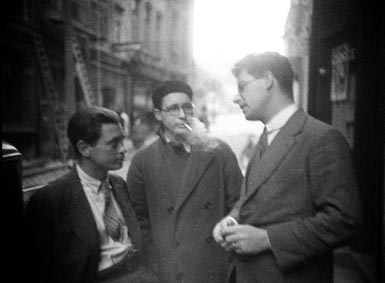

It was the beginning of the complicity between Henri Storck and the artists. Félix Labisse, to whom the filmmaker would later devote two films, wrote the scenario. The artists, seen first as friends and companions and then as characters. Ensor in his house in Ostend, Spilliaert by the sea, a country party with the Tytgats, they are all there, recorded in irreplaceable documents. When Henri Storck entered into the domain of art films, he introduced essential innovations to the genre.

In his work, he used musicians such as Maurice Jaubert and André Souris who, under his impetus, were able to create sound worlds as subtle and detailed as the images. They made it possible to listen to paintings and gave a sound to the canvasses.

He also suggested the use of fiction. André Bazin underlined the difficult meeting between the frame of a painting and the edge of the screen, the first being centripetal, closed upon itself, isolated, and the second being open to that which is off-camera and to narrative continuity. With Le monde de Paul Delvaux, Henri Storck resolved this apparent impossibility: he chose to lead the spectator around unframed paintings, shown in a coherent succession and organised into a script. They were filmed as fictional shots developing a visual world that can be read as a story.

In Rubens, Storck opened up the art film genre to a critical and didactic role by presenting in parallel the biography of the artist, his place in history, and an analysis of his works. He divided the screen into several frames so that comparisons could be made, he used animation to highlight the composition and structure of a painting, he isolated details, in short he created a cinematographic work that combined observation and knowledge.

His appreciation of art gave him a privileged relationship with the paintings: he allowed enough time to observe, and his camera movements were more like those of a wander than of a hunter.

Pour vos beaux yeux was a zany story if ever there was one, since it tells the adventures of a young man who buys a glass eye and then sends it through the post. It put Henri Storck in touch with surrealism, and he transposed its theoretical or pictorial propositions into cinema: weird situations, editing according to association of meaning or form, the enlightening disruption of reality, ferocious denunciations of the farce of History, the celebration of desire, all of this surrealist spirit is to be found in L’idylle à la plage, Histoire du Soldat inconnu, Sur les bords de la caméra,…

Festivities and brass bands

In 1930, the young Storck, designated official cinégraphiste of the city of Ostend (no other title or honour gave him greater pleasure than this kindly, solemn acknowledgment of his talent), was charged with filming Les fêtes du Centenaire. Eight minutes to celebrate his city celebrating itself. From this experience emerged his lively appreciation of folklore that would lead him, some forty years later, to record Fêtes de Belgique. The word ‘folklore’ should not be taken in the rather negative sense of demonstrations in clogs for tourists and cultural centres. He was concerned with recording real life when it erupts in jubilation, with customs that become jubilation. Like Ensor, he had a fascination for masks and local processions or gatherings. He filmed the vitality, the naivety and the malice of the popular spirit. He was inside, like the costumed participants. He was a devotee, happy because he really felt that these really were local celebrations full of sap and juice, a cathartic letting off of steam. He saw the innocence and the slap and tickle, the mixture of the sacred and the profane, the solemn and the improvised, sex and transgression.

Also expressed here is what would become one of his major concerns: to bear witness, preserve, record. The world and time pass by leaving no trace, and he filmed to counter this loss, this irreversibility. A filmmaker must bear witness to his times. One of his roles is to take an interest in major events, important social changes and try to understand and explain them. He must work on content, the documented viewpoint, and form, that is to say to magnify the subject by breathing into it the strength of lyricism, emotion, and sincerity. In his files he accumulated grand, generous projects, some encyclopaedic (a gesture of gestures), some sounding the alarm (pollution in the North Sea), some more social in orientation (the end of the steel industry), all of which remained just dreams, or unfinished…

Pure fiction

La mort de Vénus, a film that has turned to dust – alas, never again will we see this pretty person frolic in the waves with her handsome sailor lover – bears witness to the fact that fiction was a source of inspiration. In the same spirit, the successor to this engulfed goddess was a charming young woman in love with a dashing soldier in Idylle à la plage. The unfortunately disastrous release of this charming short film burnt the filmmaker’s fingers. But the temptation was there.

His scripts were called La courte échelle, Le cachot, Palazzo del mar, Les aromates suprêmes, Les surprises de l’hérédité, etc. They never went beyond the writing stage. What producer in his right mind would have put money into Storck’s marvellously extravagant, poetic and tenderly burlesque stories, which contained a world that has nothing to do with that of classic tales, conventional morals and logic? Fairy tales, sheer imagination, waking dreams, crazy playlets, anarchic fantasies, these free tales all work in the spirit of l’Age d’or. Unfortunately for the cinema, this inspiration has been lost, smothered by bans or the mistrust of financiers and perhaps also through modest and more secret self-censorship. Nevertheless, the temptations of fiction remained, though they took a more proper path, expressed with confidence under the cover of the documentaries. Fiction is present in Trois hommes et une corde, Comme une lettre à la poste, Au carrefour de la vie. It turned Permeke into a mysterious character whose mystery had to be resolved post mortem, transforming him into a sort of Citizen Kane of art. Ultimately, it came into full view in Le banquet des fraudeurs, a predictive fiction on the new Europe.

Commanding commissions

If one reads the credits of Henri Storck’s films attentively, one notices that most of them are commissioned. That is a clue to the difficult survival of Belgian cinema. What could one do in the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s when one was tied body and soul to one’s camera, didn’t have two pennies to rub together and needed to earn a living by doing one’s profession? Sometimes he managed to knock something ingenious together with his friends, using bits and bobs, and a tenacious enthusiasm. And sometimes, he looked out for commissions of any kind, from cities and mayors, professional organisations, tourism offices. A film is a film, and behind the specifications there is room for real vision, a personal work. Masterpieces such as Borinage and Symphonie paysanne, Le patron est mort, and Le monde de Paul Delvaux started out as commissions. Then there were the ministries of Justice and of Education and many other worthy bodies, and finally international institutions took over, their desire to communicate channelling public money to creative people.

All filmmakers of that generation, whether Dekeukeleire, Cauvin, or Bernhard, made their films by broadening this strict yoke. Sometimes, stormy correspondence bears witness to how difficult the meeting between institution and creator could be. What is admirable is that the filmmakers survived and that pernickety civil servants reluctantly, as if by mistake, allowed them to show and tell, surprised perhaps to then see the ugly little duckling turn into a beautiful swan. But some of them, well-informed willing collaborators, were happy to get a contract signed by some important person, a contract which may have appeared anecdotal to that person whereas he was in fact working for the anthology of cinema. They felt the satisfaction of a duty well done. To them we are grateful!

At the end of the 70s, Henri Storck – everybody knew who he was by that time – used all his influence and notoriety to open the path for younger generations by initiating the creation of the Documentary Film Workshops and the Centre for Films on Art, places he wanted to be open to experimentation, to risk taking. It was a generous transfer of vision and around him a web of relationships was woven.

Jacqueline Aubenas